Foreign Investment Law More than a Face-Saving Gesture

Image by Mona Tootoonchinia from Pixabay

By Professor Ding Yuan

Some may argue that China’s newly-approved foreign investment law is merely a gesture to ease overseas investor concerns and keep FDI flowing into China, or a rushed attempt to smooth the way to a new trade deal with the U.S. However if we look at a series of initiatives that China has been pushing forward since October 2018, the complete picture tells us that a wider opening up is underway. The new law overhauls the existing foreign investment structure and incorporates many of the innovations implemented in the Free Trade Zones. Despite many details yet to be clarified, the new law — as a framework — marks a critical and strategic turning point that makes it clear China is on track towards being a major responsible stakeholder in the world. The challenge, during implementation, will be in how the government handles the expected push back from those state owned enterprises (SOEs) that have a vested interest in keeping the status quo.

This will require careful crafting of the negative list; communicating clearly to the different levels of government the importance of this significant shift in policy; as well as moving the focus away from creating barriers to entry into some sectors, shifting instead towards allowing access that would have both domestic and foreign firms follow regulations laid out in Chinese law.

The last three decades saw a big surge by the Chinese economy and the country has emerged as the strongest and biggest manufacturer in the world. Especially after joining WTO, China became a vital player in global trade. However, its role in the global value chain was still merely that of a manufacturing base. The last wave of globalization shifted industrial power from the West to the East. And although investment was a one-way flow, both foreign investors and their Chinese counterparts enjoyed the benefits it brought. On one hand, foreign-funded enterprises in China enjoyed ‘ultra-national’ status (even more benefits than local companies) and were entitled to preferential treatment on land acquisition, employment, tax, and benefitted from loose regulation on environmental protection. On the other hand, China, perceiving herself as a developing country, focused more on developing and “protecting” Chinese industry, and so imposed many restrictions on foreign investments in the country. In today’s economic environment, the ultra-national treatment given to foreign-capital enterprises in China would not conform to WTO principles; neither would such strong governmental control over the country’s investment industry. Yet, the inadequacy of legislation was neglected by both sides while they were reaping strong economic growth and investment returns.

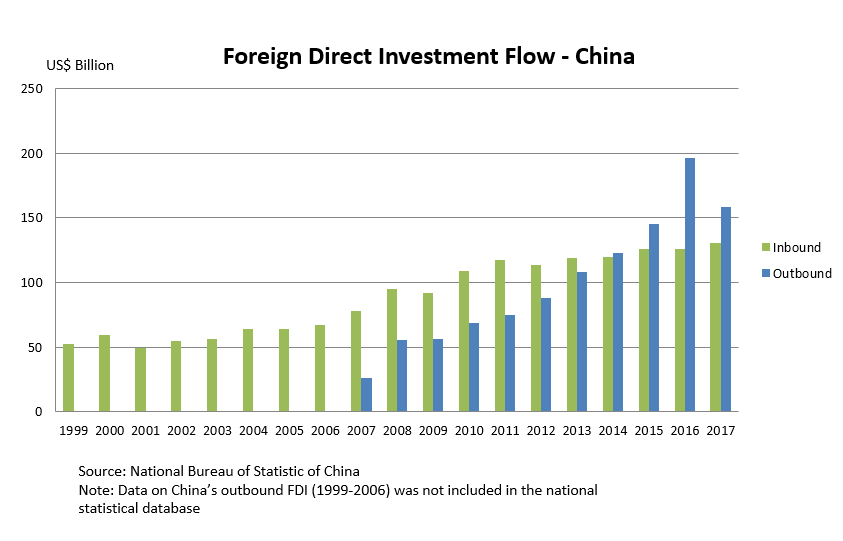

It was not until 2014 that, for the first time ever, China’s inbound and outbound FDI reached a balance of around US$120 billion, and it became a major investor in the world. However the investment environment for Chinese investors overseas turned less friendly, especially in Western countries, as concerns about less-than-reciprocal levels of market access gained more attention from their political leaders. Meanwhile domestically, when ultra-national treatment was no longer provided, the competition became much fiercer than before.

China is now in transition towards a more sustainable consumption-driven and innovative economy. In 2017 and 2018, its total retail sales of consumer goods respectively reached 36.6 trillion yuan and 38 trillion yuan (roughly $5.7 trillion), making it the world’s biggest consumer market. China is no longer merely a manufacturing base. Labour cost, tax and land use are no longer foreign investors’ major concerns. Instead, they are focused on the importance of a more open, fair and transparent environment — for all types of investors.

The Chinese government has responded to their concerns. Starting from last October, a series of initiatives have been carried out to provide a level playing field and strengthen the rule of law. China’s Vice Premier Liu He reassured the public that SOEs are in an interdependent relationship with private enterprises, and there is mutual support and cooperation. The equal treatment of both domestic and foreign investors, subject only to a negative list in certain sectors, should provide a solid legal base that fosters foreign investors’ confidence about their long-term development in China. This would then result in more and more foreign-capital enterprises becoming responsible Chinese corporate citizens rather than just utilizing China as a manufacturing base. “Made in China, sold globally” would be replaced by “Investing in the entire value chain to better serve Chinese consumers”.

The new law is a vital piece of this puzzle and the importance of the negative list, in all of this, cannot be overstated. In putting together the list, the government should resist any efforts, from state owned enterprises, to influence the outcome. The list should be internationally acceptable, which means it should include sectors commonly protected in other countries, it should not be overly lengthy or inclusive and it should focus on effective regulation of the players, rather than merely erecting barriers to entry.

Once the negative list is in place, the next hurdle will be implementation of the new law. This will be a major challenge unless the different layers of government fully understand its significance as a fundamental shift in China’s investment and trade environment. If they fail to grasp the importance of this, they will not change their behaviour, undermining application of the new law, and leaving foreign investors frustrated.

Last but not least, the new law excluded the financial sector. Although China has announced, several times, that the country will loosen control over foreign investment in this sector in the next few years, this continued exclusion is somewhat disappointing. Many of the challenges being faced within the sector are not because of inclusion or exclusion of certain types of players, but missing regulations and a failure to consistently enforce those that do exist. In combating shadow banking, for example, the biggest challenge is continuous regulation. China should take a normalized approach to the financial sector and move from regulation by entry and shareholding percentage to regulation in licencing and operations. Those who enter — as well as domestic players — should play by the rules if they wish to reap the benefits. Foreign companies legally recognized as Chinese entities, with Chinese operational licencing should be subject to Chinese regulations that also govern domestic firms.

The new law will come into effect on January 1, 2020. The most critical step, over the next nine months, will be how the Chinese government steers new avenues to strengthen legal enforcement. We hope legislators will engage in extensive consultation and solicit input from industry stakeholders, that the negative list will be highly effective, and that clear procedures and mechanisms can be set up for efficient implementation.

Ding Yuan is Vice President & Dean of CEIBS.

Research Fellow Cui Xiang also contributed to this article.

It was published by Caixin Global on March 29.